When you move to a new, fascinating region, first you are pleased. Many new things are usually perceived as exciting, assuming you came voluntarily. If you were someone persuaded to relocate or had to travel, this phase of honeymoon may not happen.

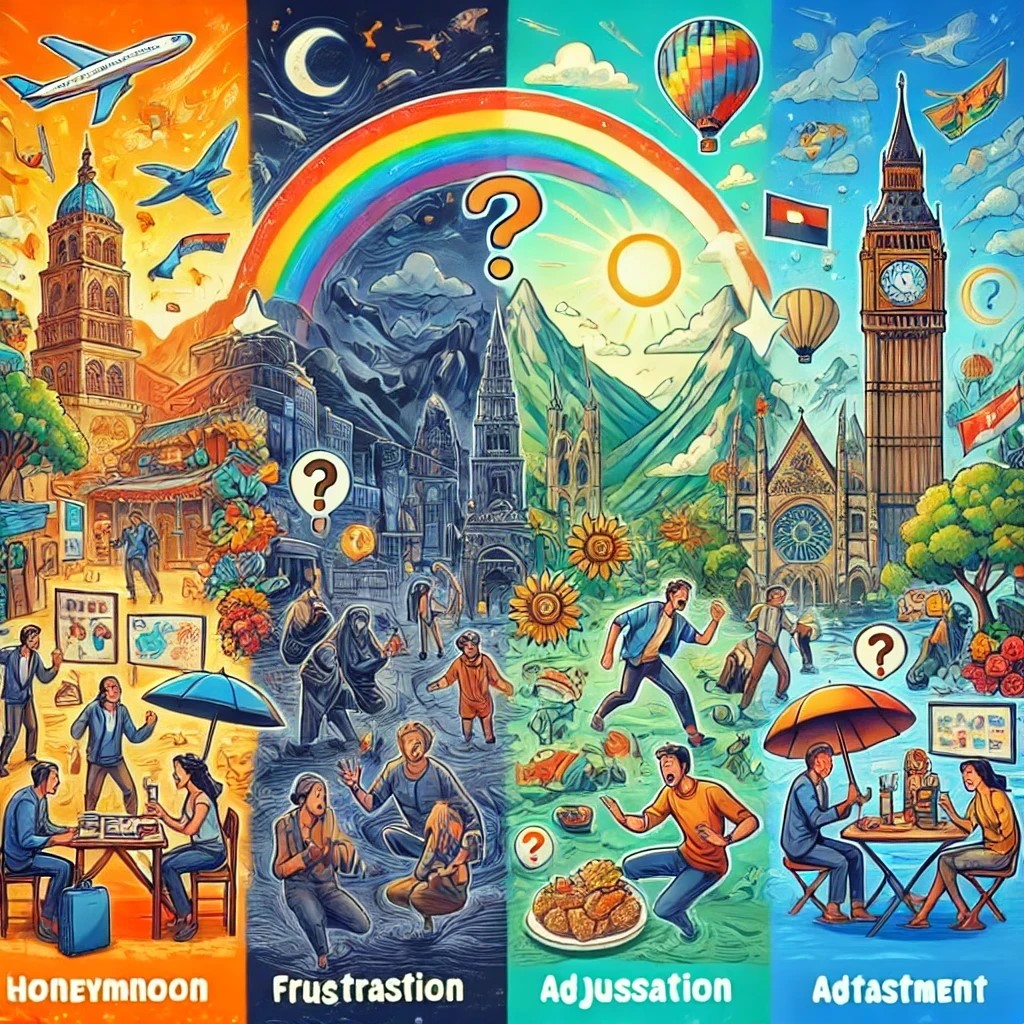

The so-called culture shock consists of four steps:

- Honeymoon

- Frustration

- Adjustment

- Mastery

After the Honeymoon – a phase that can last from several weeks to several months – often comes a stage of disillusionment and frustration. You enter into everyday life with all its dissimilarities: people appear e.g. slow and not really willing to work. The bureaucracy, inevitable in a foreign country as a foreigner, can’t be understood, is oddly organized, many papers are required you have never heard of (here, for example, you must always legalize your signature at the town hall).

Courtesy formulas are different and cryptic. In most cases, you have to learn a language and the beginning may have been relatively easy, but now other people are disappointed that you don’t know this or that phrase. And so on, we could add many examples without end.

As I explained in the first article, shock is the wrong word (used by Cora DuBois in 1951 for the first time). Confusionwould be better: The culture (see explanation here) I know is no longer correct. People behave differently than I expect. And they expect a different behaviour from me too, and I am not able. The intuitive rules that I have learned from my parents and from my surroundings, do no longer apply.

Examples

- As a German, I’m used to communicate relative directly. A phrase like “I don’t like this or that” I can easily say to friends or even at work. In Africa and other regions that’s very rude. Especially elderly people I honour by agreeing with them (almost always).

- “Isn’t it a good idea to do this or that,” says an American superior to his German employee. The German thinks: Good idea, yes, but I don’t agree that this would work. But, the American uttered a commandment.

- An African in Germany does not squeeze the other’s hand while greeting, but only holds his hands and touches the other one: as he does at home. This is interpreted as weakness.

- Americans often tell a lot about themselves during the first visit. In the United States it’s normal to look for common ground to get to know each other. So you have to tell a bit about yourself. In Europe, the stories from your own life are perceived as arrogance and boasting.

After the phase of irritation you get slowly into the third period of adjustment or adaptation. Sometimes it’s also called recovery, but I don’t think that this fits. You come to know the new culture. Again and again there occur irritating experiences and crises, but you learn more and more how to deal with it.

Often a friend can help here who has gone either through similar steps (e.g. countrymen who have been longer in country or locals with experience abroad). You learn to ask questions that help. Frequently, these look differently as you know from home: more indirect or more direct, as you may know. More specific or less specific than at home, depending on the context.

At this stage, it’s important to think specifically about the new culture, language and characteristics of the country and to do research. Ask questions, but also maintain reading, researching and maintaining contacts can help. How things are done in practice depends on the country.

But here again some examples:

- Here in Africa you have to take your time and “sit around” in a café. We should not do anything too fast. Asking questions is allowed, but the answer may not help. Therefore, you should ask the same question more than once to the same person or to several friends at the same time.

- In Germany and France questions are good and it’s part of courtesy to ask. Who doesn’t ask directly, is not interested. As many people have experience living abroad, you can ask them directly, but politely, about their experience. Especially dealing with authorities can be frightening. You can ask friends if they accompany you.

In the final stage of “overcoming” or “mastery” (Wikipedia) you are immersed in the new culture. You understand what is happening, even if you can’t always respond correctly. You can intuitively classify things and interpret them correctly, even if you don’t like them or you continue to have problems with them. At the end, we remain foreigners.

Many who survived well the so-called culture shock know to talk more accurately about the culture of their host country then the locals themselves. They do express their observations very often in words the locals would not use, but they know to identify things quite exact. Especially when someone is analytically gifted, he can summarize his experience very well and precisely. This is often appreciated by locals too.

A particular speciality are people who have lived abroad for longer, and then come back home: They often experience the so-called “re-entry shock”, a “re-integration shock”. Their personality has changed abroad, but their country has also. After two to three years this difference can be so serious that someone has a “culture shock” because his “home” became a “strange” place.

This irritation may be much more violent and more difficult to overcome than the normal culture shock abroad. Firstly, old friends very often do not understand him or her: “You’re back home!” And often the person concerned doesn’t think himself about the differences and is not aware of the problems.

Therefore, we will devote a separate article this phenomenon.

by Arne